from Women in Sound #7

illustrations by Maggie Negrete

The first installment of this article can be found in Women in Sound issue 6.

----------

In part one of this article, we examined the layout and main features of an input channel strip, following the path of signal flow from the preamp to the channel fader. Now we’ll dive even deeper into some extra features on the channel strip and cover the VCA, Master, and Monitor sections of an audio mixer.

Let us revisit the top of the channel strip, where we may find a polarity switch with a crossed-out circle like this: ⌀. Engaging this switch will reverse the polarity of the incoming signal. Most often, when miking snare top and bottom, an engineer will engage this switch and “flip” the polarity on one of those input channels so that each snare signal arrives at the mixer in-phase with each other. When a snare is struck, sound waves are produced from the top and bottom drumhead. Since the waves are heading in opposite directions, it's very likely that they’ll be out-of-phase with each other once they reach the mixer, which will make for a weak snare sound in the mix. Of course, this is not always the case, and we generally must rely on what sounds good to our ears in order to decide which channel’s polarity should be reversed.

Also near the top of the channel strip we may find a direct out option. Direct outs send a copy of the input signal to a physical output of the mixer before it has undergone any processing in the channel strip. Direct out is commonly affected by gain, phantom power, and polarity. Again, this will vary depending on the mixer’s manufacturer. Direct outs allow us to provide unprocessed, raw, multi-track recordings of a performance. We could also easily duplicate a stage sound by sending its direct out signal straight into an empty input channel, allowing us more versatility in parallel processing. This is when we incorporate a clone of an audio signal — in this case, the direct output signal — running alongside the original sound. The clone is generally processed in a different way from the original with the goal of enhancing the overall sound. The direct out is sometimes engaged by a switch, but it could also be a rotary knob, allowing you individual control over level being sent directly out.

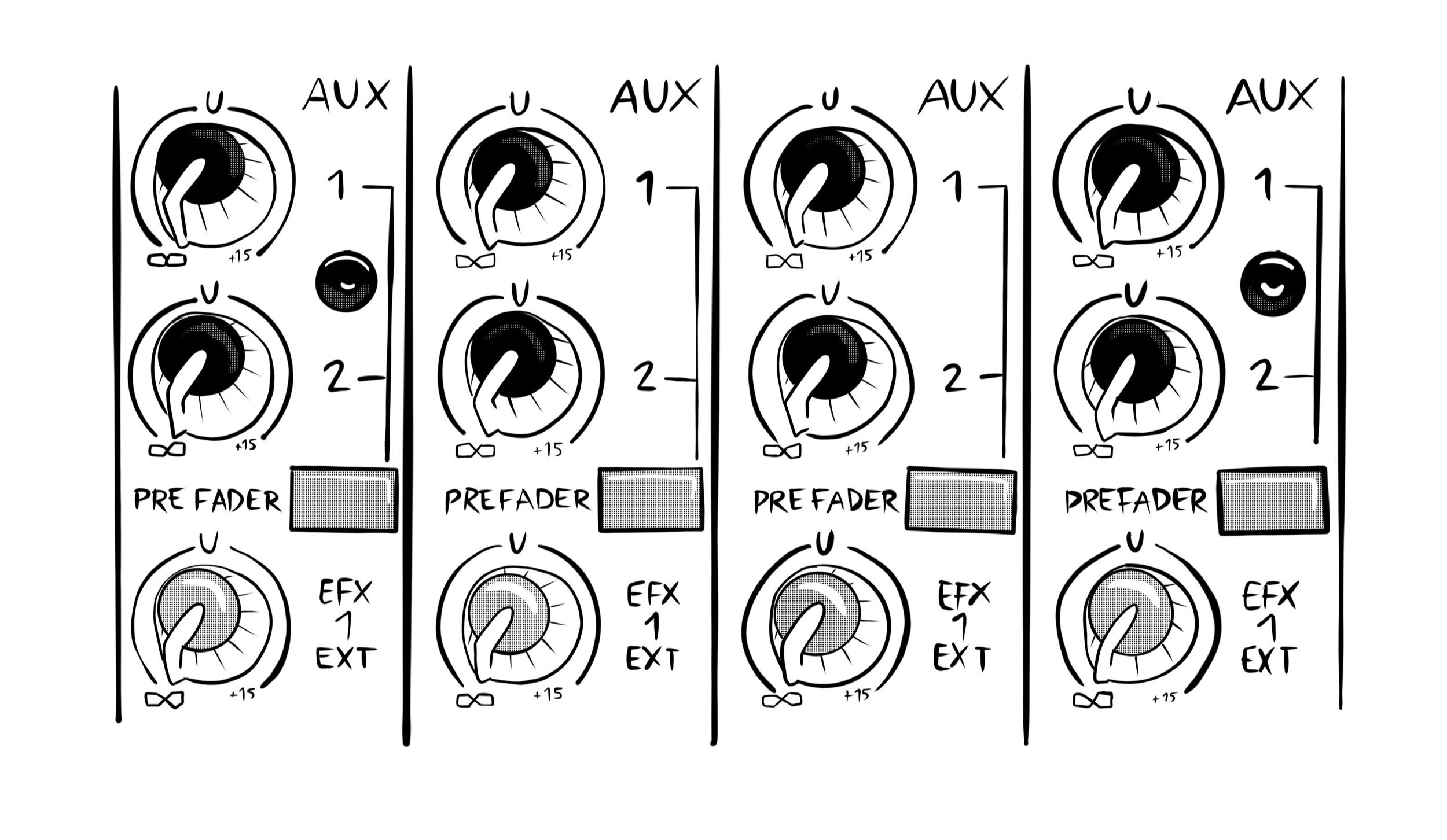

Now let’s talk about pre-fader and post-fader switches. You might find one next to the direct out, but most commonly, you’ll find these next to the auxiliary sends. Remember that before the signal reaches the channel fader, we have the option to make a copy and send it to various busses in the aux send section.

auxiliary sends with a pre-fader switch: Remember that before the signal reaches the channel fader, we have the option to make a copy and send it to various busses in the aux send section.

There are some classic scenarios where an engineer would need the aux signal sent either before reaching the fader (pre-fader), or after it passes through the fader (post-fader). Here’s a common one: You’re ready to soundcheck, mixing monitors from front-of-house. You’re sending kick to the drummer’s monitor, but they don’t hear anything. You swear you’re sending on the correct aux and the amps are on, but, wait, is the fader down on the kick channel? If the answer is yes and auxes were set to post-fader, then that signal will not reach the drummer until the channel fader is brought up. Basically, we want to make sure our front-of-house mix movements, such as moving faders up and down, do not affect the musicians’ stage mix levels. Thus, we select the stage mixes to be sent pre-fader.

Post-fader can be useful when using auxes for driving effects. We generally want the level of certain effects to maintain a steady ratio with their dry (unaffected) signal. Let’s say we’re sending a vocal to a reverb via an aux send. If we need to lower the vocalist’s volume during the show, we want to make sure the reverb follows in the same direction — that is, if we’re trying to achieve a natural vocal sound. On the flip side, if we have to push the vocal, we commonly want the same amount of boost going to its reverb. Therefore, post-fader must be engaged.

The same concept applies to direct outs with a pre/post option. For example, a Midas Heritage 3000’s direct out, by default, is derived from the input channel post-EQ and pre-fader. This means the engineer’s EQ movements will flow into the direct out, but the channel fader movements will not. If we engage the “pre” switch on this desk’s Direct Out, the signal will then be extracted pre-EQ, pre-insert, and pre-mute. Note that the physical switch on this analog desk only reads “pre.” Remember: No button, fader or knob will explain exactly what is going on underneath, but the manual usually will.

insert send and return: points in the channel path where the signal is broken off and sent to an external destination, then returned back in, resealing the breakpoint and continuing its course.

Speaking of pre-insert, this refers to an insert point, otherwise known as the insert send/return. Inserts are points in the channel path where the signal is broken off and sent to an external destination, then returned back in, resealing the breakpoint and continuing its course. On most mixers, this means the insert send physically leaves the console through a TRS ¼” or XLR output jack. The engineer can then use a Y-cable to send the signal to an external dynamics or effects processor, and return it back into the same jack. Consoles like the Midas Heritage will provide a choice to place the insert either before or after the EQ section via its pre switch.

Returning to the bottom of the channel strip, we find more options for bussing the signal to our desired outputs. In the most basic mixer set-up, we want the signal to reach the left and right busses, as those will usually be driving the left and right speakers. This is normally routed via a switch near the bottom of the channel strip, which is usually labeled something like “ST” (stereo), “LR” (left/right) or “Main.” It is a common mistake for engineers to accidentally leave this switch disengaged, so make a point to check this when there’s no signal hitting the main speakers. Along with the L/R routing switch, you may find a mono bus routing switch, which sends an additional copy of the signal to the mono bus output. The mono bus output of a mixer could be used to drive a subwoofer, center fill or any auxiliary speaker output.

In addition to the L/R and mono bus routing switches, we’ll also find options to route to groups, also known as subgroups or submixes. The engineer may route as many channels of their choosing to one or more group output channels. Perhaps we find it necessary to compress all of the guitars in our mix together, using one compressor, instead of inserting a compressor on each guitar channel. One solution would be to route the guitars to a group, then insert the compressor on the group. Some engineers find it useful to route all of the vocals to a group, so they can be processed and controlled on a single fader.

Y-cables are commonly used to send the signal to an external dynamics or effects processor, and return it back into the same jack.

This brings us to another important element of the audio mixer, the VCA section. VCA is a term that comes from analog electronics. It stands for voltage controlled amplifier, but don’t let that scare you. You’ll find these on digital consoles, too, but under different names like control groups (Digico SD) or DCAs (X32/M32). They’re all the same. The main concept to understand about VCAs is that they merely control faders and no audio passes through them. They have a fader and a mute switch, and they can control any input channel of our choosing. Let’s say we’ve routed the string section (violin, viola, cello) to a single VCA fader. When we move that VCA fader up and down, the current levels of all string channels routed to the VCA will also move up and down.

If certain important fader channels are hard to reach, route them to a VCA, since the VCA section is usually in the middle of the console (analog) or top-most layer (digital). For example, I like to put my important effects returns on VCAs so I can have immediate control over them during the show. VCAs are great spots for house music, talkback mic — anything that improves your workflow. Check out Dave Rat’s “Live Sound Mixing Strategy” on Youtube, where he scribbles on a whiteboard and talks about using VCAs in tandem with Groups.

By the way, are you still trying to send kick to the drummer’s wedge, and they’re not getting anything, even though you’ve brought the kick channel up in post-fader mode? Well, did you check to see if the kick was routed to a VCA, and if so, is that VCA fader down or muted?

Now we’re ready to cover the master section. We know that the input strip contains many options for bus routing through auxes, groups or left/right/mono. The master section is where we apply finishing touches to these buses before they physically leave the mixer. Here you’ll find left/right/mono, group and aux master sections, each with their own faders, processing and routing options. On more robust mixers, we will find the matrix, a powerful routing tool that allows the engineer to create multiple submixes from their choice of sources in the master section. Referring back to the Midas Heritage, you’ll find eight matrix send knobs above the left/right and group channel strips. These send knobs correspond to eight physical matrix outputs on the back of the desk. Through those outputs, we are able to send signals to various destinations, for example: the back of a venue, a different space within a building like a lobby or a downstairs bar, or to a camera feed recording a performance. The matrix also has its own set of master faders, processing and pre/post options.

Lastly, there’s the monitor section, also known as ctrl room, where the engineer monitors inputs and outputs. Some monitor sections will have a built-in oscillator, which can be sent to various outputs for testing and verification purposes. It is common practice for front-of-house and monitor engineers to use this oscillator to send pink noise through their current outputs in order to verify connection. We’ll also find the solo bus master control, where we can choose where to route all solo-ed signals. The solo bus is commonly routed to the mixer’s headphone output by default; however, it could also be routed to nearfield speaker monitors or a monitor engineer’s cue wedge. In short, the solo bus exits the console through one or more physical outputs, which can be configured in the monitor section.

Throughout this article, I’ve laid out the sections of an audio mixer mostly from an analog perspective, as I find this to be the most logical way to explain how each component relates to signal flow, but all of these concepts and terms also apply to digital desks. Read the manuals, study the schematics, watch the YouTube videos, and you’ll be able to operate any mixing board, digital or analog, with the knowledge and confidence to have a successful show.